As a startup, one of the biggest challenges will be the pricing of your initial product. You’ll fluctuate between a concern that if you price it too highly the product won’t stick, but if you price it too low, it will be impossible to build a sustainable business around it.

It may be tempting to look for equations and projections to find the best price. But the big secret here is that pricing isn’t a math problem: it’s a judgment problem. All businesses have prices, but most overlook pricing strategy. 85% of businesses report that they do not use thought through pricing strategies. What’s the alternative? Guessing, I guess!

Something that we’ll keep coming back to in this article is that price is your strongest signal to buyers about the quality of your offering. It is not the other way around, where your quality offering justifies a high price.

That makes pricing a marketing positioning tool as well, and the long-term health of successful startups comes from understanding the critical role of pricing in your go-to-market and brand strategy.

What is product pricing and why is it important?

To borrow from Ries and Trout in Positioning: The Battle For Your Mind, who coined the phrase back in 1980, product pricing is “a marketing method for creating the perception of a product, brand, or company identity.”

If you think about it, as a startup, if you wanted to identify your brand as a premium one, how do you go about it? It’s how you price the product that tells your customers the kind of business that you are.

There are three elements of market positioning that, combined, will help you to determine where to price your product:

- Customer: what value does your offering create for them? saving time, effort, taking away a risk, etc.? What signal do you want them to receive?

- Competition: how much value do you create relative to your category? Are you within the norms for your category that customers have come to expect?

- Company: what are your values and how do they align with your customer's and stand out amongst the competition?

Just remember that pricing is psychological. It is a way of telling your customers how much your work is worth.

The Pricing Power Of Economic Value Analysis

One of the most effective tools at Price Theory, especially for SaaS businesses with few competitors or a very unique product offering, is to look at it through the lens of economic value analysis. This is where you consider how much time and effort that you’re saving the customer, and use that as a baseline for a fair percentage take.

In the SaaS space, which we occupy, you would make that calculation like this: total up the direct cost savings, time saved by employees (consider their salary the cost), the savings on the production and management of tools, risk mitigation, and the other ways that your solution adds value. Then, with that total number, determine what is a fair price to take of it.

Ideally, your fair share of that total economic value will be around 10-20 per cent. Anything less than 10 per cent and you’re undervaluing what your solution brings to your customer, and anything over than 20 per cent will result in your customers questioning the value that you’re bringing to them (it’s amazing how consistently the threshold is proven to be 20 per cent on this).

Take, for example, a SaaS solution that impacts the work of three employees with a yearly salary of 100K (on average). Your software makes them 50% more efficient at their job, so the total economic value would be 150K (100K*3 employees*50%). You could then justify a yearly cost at 20% of that (30K) for your SaaS product.

What this gives you is a fair price, along with a narrative about the value you create for your core customer. Especially in the B2B world, a rational proposition such as “we typically see about 150K in time costs for our customers” goes a long way.

Other Common Pricing Strategies

Value-based pricing is just one approach to pricing, and different sectors often use different pricing methods—often in combination with value-based pricing—that work for their particular customer base. There is no “silver bullet” approach to pricing that is going to be equally effective in every situation.

Some of the more common approaches to pricing include:

Cost-Plus

One of the most straightforward forms of pricing, cost-plus pricing is when a fixed percentage is added on top of the cost that it takes to produce one unit of the product. If it costs $1 in total materials to brew a small cup of coffee, then cost-plus pricing would be to add 20 per cent and charge the consumer $1.20 for the coffee.

The benefit of cost-plus is that it is extremely simple, which has been key to its widespread use. However, the downside is sizable in terms of lost opportunity: this method does not take into account how customers will perceive the quality of your product based on price, nor does it take into account how it will be perceived relative to any competitors.

Competitor-Based

Competitor-based pricing is when you set your pricing specifically in relation to your competitive set. You notice that your competitor is selling their coffee at $2, so you decide that you should sell yours for $1.90. In competitive markets it is extremely important to set a price that is not outside of norms for the category. If someone was selling coffee for $0.10 you might think “what’s wrong with this?” and conversely if they were selling it for $1000 you might think “that’s outrageous!”

But while competitive pricing is useful, new industries and types of offerings may not have competitive norms to fall back on. Also, remember that 85 percent of companies are not doing their homework when it comes to pricing strategies—not a great track record!

The other problem—and one that faces startups in particular—is that many of their competitors will be able to leverage economies of scale to keep their costs down, and may well be able to sell their product at a cost that isn’t profitable to you, meaning that a purely competitive-driven pricing point might result in you selling at a loss while they remain profitable.

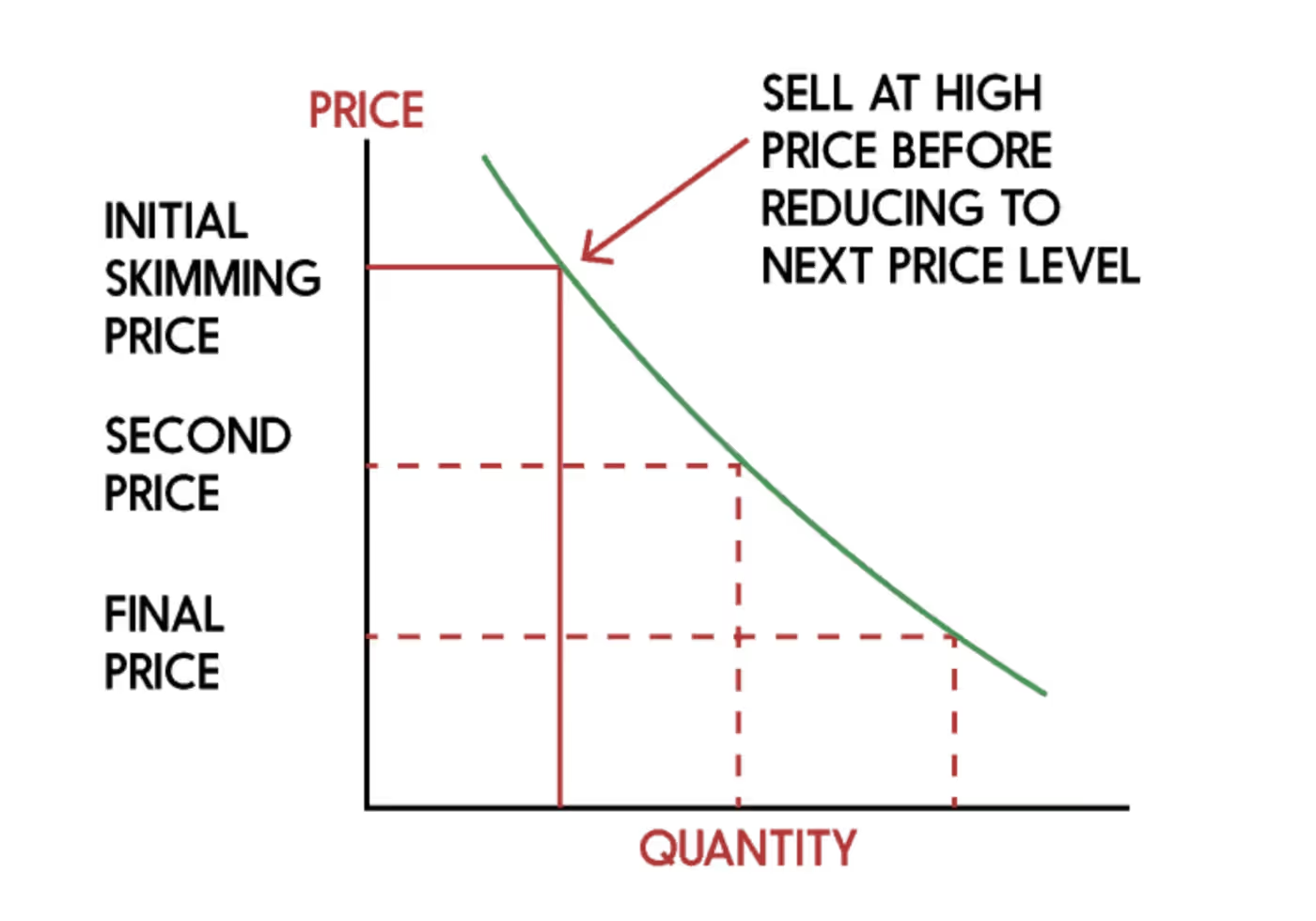

Price Skimming

Price skimming describes an ongoing pricing strategy where you enter the market at a high price point, and then, over time, slowly “skim” the price down as more competitors, products, and innovation enter the market. We see this frequently in the consumer technology space; a new, maximum-spec computer might cost $3,000 when it is first released, but a year later the price would have been steadily reduced to $1,000.

Price skimming can be extremely effective for offerings with a high level of awareness in its market (so not typically a startup). Otherwise, to use this strategy effectively you must have compelling value differentiation and have identified a well-defined and relatively small market entry segment.

Penetration Pricing

Penetration pricing is the opposite pricing strategy to price skimming. With penetration pricing, you introduce the market to your product or service by pricing it at a steep discount, and use pricing to win customers and market share. Then, as you create brand loyalty and customers are happily using your services, you can start to pull the price up to the optimal sustainable price or benefit from economies of scale. Penetration pricing is only advisable in specific scenarios, though, and only if you have a sizable financial backstop to subsidize your low price.

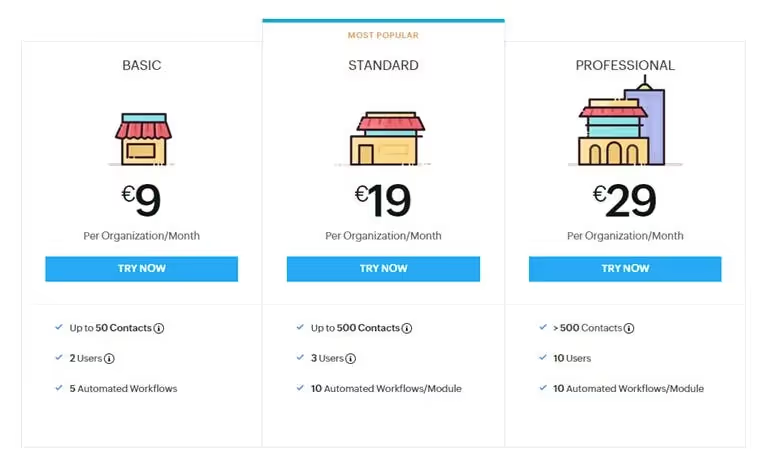

Price Tiers

Using price tiers is another common pricing tactic in SaaS, where subscribers have a choice between several different price points and bundles of features. Typically this is used to “anchor” prospective buyers in higher or lower prices, and push them to a middle “just right” option.

The best use case for price tiers, however, is really for addressing different customer segments with distinct needs. Take photo editing software, for example: Students vs Amateurs vs Design Agencies may all get different value from using the software, and different price tiers can be designed to address differing willingness to pay.

Outside of having multiple core customers, we typically recommend simple, straightforward pricing to serve as a strong signal to your buyers.

How to price your product—Price Theory In Action

Once again, there’s no hard-and-fast mathematical formula or system that will be universally effective with pricing. However, there is a best-practice methodology and approach to pricing that we have used ourselves to good effect, and will be a useful way for most founders to consider their own pricing strategy.

1) Know the customer:

It starts with understanding your core customer, and how your offering will create value for them. A lot of startups get hung up on their inability to collect the most detailed data at this point. However, a good estimation based on qualitative research is usually more than sufficient, in this instance, to undertake a value-based approach to pricing.

2) List how you create value:

Once you’ve got the customer profile, the next step is to consider all of the ways that your product creates value for them. It’s a good idea to be able to quantify this with numbers to have a sense of what your product is going to be worth.

Generally speaking there are five kinds of value to look for:

- It replaces something your customer would build for themselves.

- It saves time and/or makes tasks more efficient.

- It reduces a risk (such as a lawsuit or inventory spoilage).

- It unlocks a new source of revenue for your customer.

- It has direct savings to business operations

At this stage, if you find that your offering is not creating sufficient value for your core customer, then it may be time to go back to step 1 and search for a different or more refined target.

3) Take your fair share

Consider how differentiated and effective your offering is. Are you a little better? A lot better? Category-redefining better? Take your fair share of the total economic value (somewhere from 10-20 per cent) based on how differentiated you are to your core customer and how competitive your market is.

A combination of desktop research to understand the competition dynamics, and a few key customer interviews to understand their pain points and the depth of value that you’re promising to add to their experience is enough information to arrive at the right price for your product.

How to choose the right pricing strategy for your startup

A mentor once said to me that pricing is not a math problem, but rather a judgment problem. It has stuck with me ever since, because it’s very true: there are no hard-and-fast formulas that you can apply to come up with the ideal pricing for your product.

It’s better to remember three principles that will guide the pricing of the product. The first is to understand the value that your product offers to a customer. The second is to understand that your price is always going to be your strongest signal to convey that value. The third is to understand the impact that the competitive landscape will have on your pricing.

This is hard to get right. Remember, 85 per cent of companies are not happy with their pricing, and that applies to enterprises with all the resources that they have access to as much as it does a startup. However, it is mission critical to spend the effort in pricing in order to have true conviction behind your strategy.

Ultimately, the better you understand your customer and the impact your product will have on them, the better placed you’ll be to extract maximum value and establish a fierce loyalty in your brand from its earliest moments.